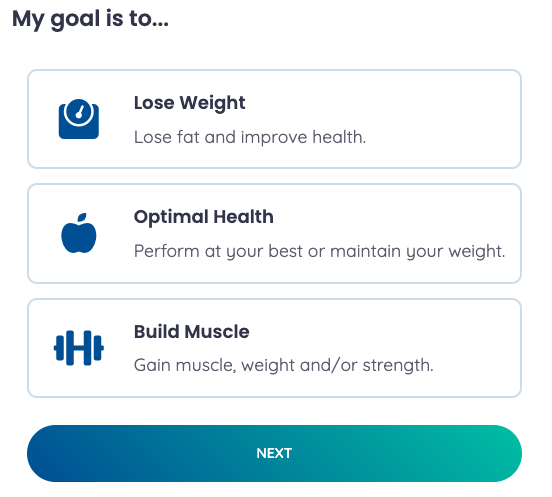

The biggest difference between Health Evolved and many of the other weight loss or weight management programs is this…

You will evolve to a healthier lifestyle without fear of ‘springing back’ to your old habits. You will have confidence that the weight you’ve lost, the new activities you partake in, and the delicious food you’ve learned to love are NOT a fad. They’re a part of you.

We achieve this through healthy habit formation. Through education, reflection and strategy implementation, we work together to create a lifestyle that truly WORKS FOR YOU.

Remember: if you start out a program that feels hard to maintain, you WILL spring back. Our bodies and brains naturally do not want to be under stress (or doing hard things). When the program that strains you is over, you will revert to old habits and BAM – weight gain and the host of other health issues you once suffered from return.

In this week’s blog, we wanted to share an insightful article written by Dr. Rebecca Richards, PhD. CPsychol. (@drbeckyrichards on Instagram; @drbeckyrichards on Twitter).

Rebecca is a Chartered Health Psychologist, a postdoctoral researcher with the University of Cambridge, and obesity, metabolic health & behaviour change specialist. This article covers a model behind successful weight loss maintenance – how to lose weight and keep it off.

Enjoy!

—

Hundreds of research studies support this cycle of weight loss and regain. Following (non-surgical) weight loss interventions, on average, people regain around a third of the weight within a year and the rest within 3-5 years 1-2. But some people do lose weight and manage to keep it off. So what’s their secret?

In 2017, researchers from the University of Exeter conducted a review of 26 previous research studies from five countries with 710 participants, which explored people’s experiences of weight loss maintenance*3. By collecting and analyzing the findings from these studies, the researchers were able to find out how these people had managed to keep the weight off.

A Model of Weight Loss Maintenance

Based on their findings, the researchers proposed a model of weight loss maintenance. Their model proposes that making the necessary behaviour changes required for weight loss maintenance (e.g. practising dietary restraint, being physically active) creates a psychological ‘tension’ – i.e. a constant mental battle. This tension is thought to be created by several issues, such as:

- The need to constantly override old habits that caused the weight gain in the first place

- Having unmet psychological needs, which they used to meet with behaviours that contributed to their weight gain (e.g. emotional eating to get rid of sadness, anger, and boredom)

- Having conflicting self-identities i.e. the ‘old’ versus ‘new’ self (e.g. a caring parent/spouse who used to show their love through providing unhealthy food to the family)

- Negative thoughts and beliefs about weight management (e.g. viewing weight management as rule-bound and rigid, invoking a sense of deprivation)

The researchers likened this psychological ‘tension’ to a coiled spring. And so, it makes sense that successful weight loss maintenance can be achieved by managing or (ideally) eliminating the psychological tension – i.e. releasing the spring (see Figure 1 3).

Managing the Tension

Findings highlighted four key ways that ‘maintainers’ managed the ongoing psychological tension:

1) Gaining knowledge and experience in weight management

- Maintainers became knowledgeable about the different influences on their weight-related behaviours (e.g. personal attitudes, emotions, personal needs, other people and external circumstances)

- They learned from their experiences of success and failure (lapses) in weight management. When they made mistakes, they learned from them and moved on, and they found what works for them.

2) Use of self-regulation strategies

- Maintainers reported using strategies to monitor and regulate their weight. For example, they regularly checked their weight (e.g. using weighing scales, clothing fit), set targets and goals and monitored the outcomes and made plans to deal with ‘high risk’ situations.

- They set boundaries for fluctuations in their weight (e.g. + 5lbs).

- They practiced flexible restraint – eating and physical activity plans were normally flexible, but if they lapsed and their boundary weight was reached, maintainers, took action to compensate for the lapse. They would become more rigid with their diet and physical activity plans until they lost the regained weight.

3) Management of internal and external influences on behaviour

- Maintainers found ways to address internal influences that increased their psychological tension, like impulses to overeat, stress or low mood. For example, some maintainers planned their meals for the day in advance to avoid impulsive eating.

- Maintainers also managed external influences, such as social pressures to overeat, like holidays, social eating events or unhelpful comments from peers. For example, some maintainers engaged their family and friends in their weight management behaviours, and others chose not to attend social eating events.

4) Renewing motivation

- Maintainers found new sources of motivation to maintain their new weight, as initial motivators for their original weight loss decreased (e.g. positive feedback from others decreased over time). For example, some were motivated by not wanting to return to their old self, whereas others set goals or took on new roles that required maintenance of their lower weight.

- Importantly, maintainers enjoyed and found satisfaction in their new lifestyle, particularly with physical exercise, and depended less on ‘external’ motivators, such as attending weight loss groups.

While managing this ongoing psychological tension is a great start, ideally, we want to eliminate the tension as much as possible so that maintenance feels easy and second nature. Fortunately, the researchers identified individuals who had achieved this. So how had they done it?

Eliminating the Tension

Findings highlighted three ways the psychological tension can be reduced or resolved:

1) Develop automaticity

- Their weight-management behaviours (e.g. regularly weighing, being physically active) and patterns of thinking (e.g. reacting positively to lapses) became more automatic over

time. Maintainers, therefore, relied less on motivation and mental effort to carry out these behaviours because they had become habits. - They had used habit-changing strategies to break old, unhelpful habits, such as identifying triggers and using self-talk, distraction or other techniques to override the old habits.

- They also used cues and reminders to establish new, helpful habits. For example, some put their running shoes by their bed to step into each morning.

2) Meet needs more healthily

- Maintainers found a way to meet their psychological needs without using food. For example, some used exercise to de-stress or provide a ‘high,’ whereas others used distraction or relaxation techniques. Similarly, maintainers experimented to find alternative activities to address emotional eating.

3) Change beliefs and self-concept

- Successful maintainers tended to view weight management as a long-term change in lifestyle rather than a short-term, challenging project.

- They adopted a forgiving and positive attitude in the face of lapses. Lapses weren’t believed to be disasters. Instead, they thought of lapses as events to learn from.

- Ultimately, maintainers changed the way they saw themselves. They experienced a sense of liberation and increased personal control, increased confidence and self-esteem. They felt less preoccupied with their weight and body image. For many, physical activity became an important part of their life, and not just as a weight control strategy. Maintainers described a sort of ‘evolution’ into a new person with a different outlook, priorities and pursuits and realized they had the ability to change other areas of their lives if they wished.

What I want you to take away from this study is this; underpinning these factors is continued effort over time. It’s as simple and as difficult as that. The most important strategy, in my opinion, is persistence.

Article References:

[1] Avenell, A., Broom, J., Brown, T. J., Poobalan, A., Aucott, L., Stearns, S. C., … & Grant, A. M. (2004). A systematic review of the long-term effects and economic consequences of treatments for obesity and implications for health improvement. Health Technology Assessment, 8(21)

[2] Dansinger, M. L., Tatsioni, A., Wong, J. B., Chung, M., & Balk, E. M. (2007). Meta-analysis: the effect of dietary counselling for weight loss. Annals of Internal Medicine, 147(1), 41-50.

[3] Greaves, C., Poltawski, L., Garside, R., & Briscoe, S. (2017). Understanding the challenge of weight loss maintenance: a systematic review and synthesis of qualitative research on weight loss maintenance. Health psychology review, 11(2), 145-163.

—

Thank you to Dr. Rebecca for allowing us to share this article. To see more of her insights and work, please follow her on social:

Instagram: @drbeckyrichards

Twitter: @drbeckyrichards

– Dr. Dan